Every spring, foragers wait for that unmistakable moment when the forest floor reveals its treasures: morel mushrooms. With their honeycomb caps and earthy aroma, morels have earned a reputation as the crown jewel of wild foraging.

They are prized not only because of their rich, nutty flavor but also because of how elusive they are. You can’t cultivate them on a whim like oyster mushrooms or shiitake. Morels demand very specific forest conditions, and that mystery is part of their allure.

The truth is, successful morel hunting isn’t luck. It’s knowledge—knowing which forests, which trees, and which conditions set the stage for their sudden appearance.

Morel Ecology and Its Growth Triggers

To find morels, you need to understand what sparks their emergence. These mushrooms don’t just pop up randomly; they respond to very precise ecological signals.

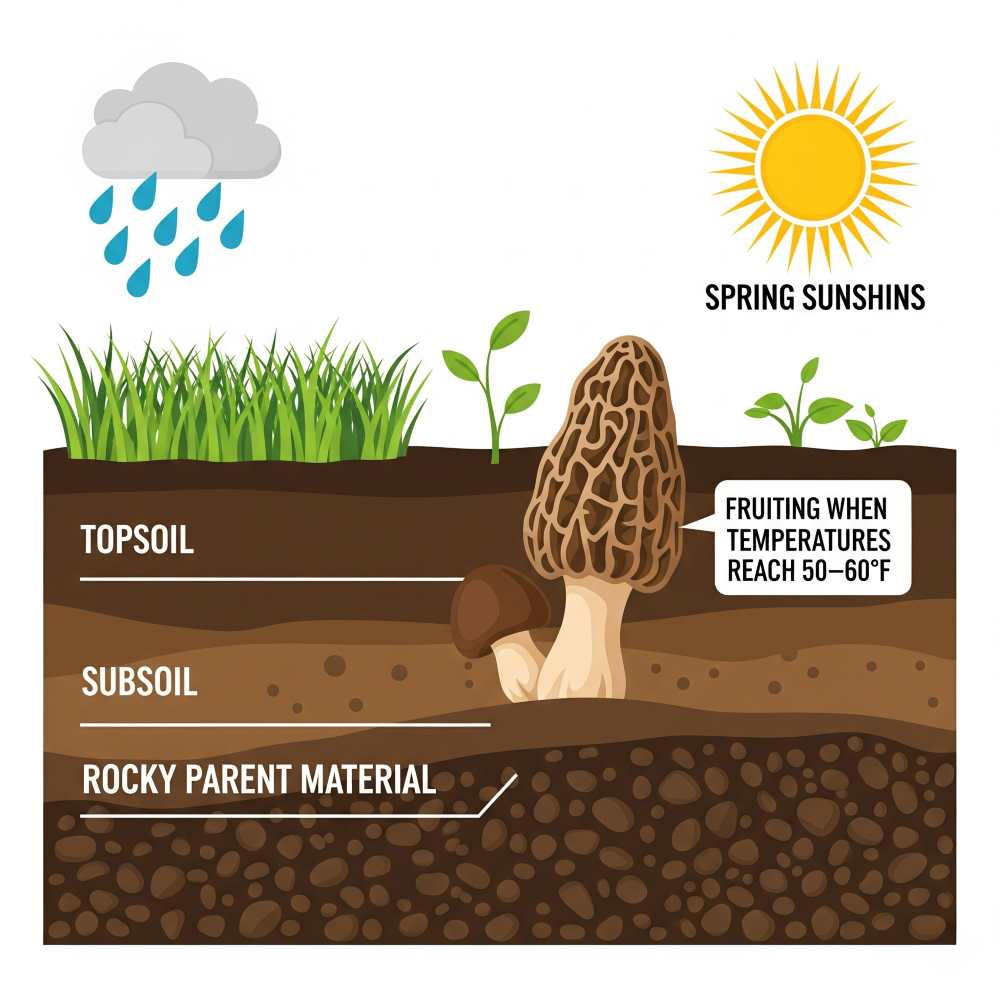

The first and most important cue is temperature. Morels typically emerge when the soil warms to around 50–60°F, often after spring rains saturate the ground. Moisture is essential, but standing water kills the flush—what they want is damp, well-drained soil.

Forest disturbances are another powerful trigger. Research from the U.S. Forest Service (Amicucci et al., USDA, 2006) notes that morels often appear in large numbers after wildfires or logging events. These disturbances disrupt soil layers, release nutrients, and create canopy gaps that allow just enough sunlight to warm the forest floor. That’s why post-burn sites in the western U.S. can yield legendary flushes of black morels.

They act as pioneers or early colonizers, temporarily taking over the area while the forest begins to regrow.

This process is part of a natural cycle. Morels dominate for a while, but eventually other fungal species come in and take their place as the forest heals. Studies on forest ecology confirm that morels are an important part of this regenerative cycle, thriving in these temporary, changing environments.

From my own hunts, I’ve noticed that you have to think like a mycologist. Ask:

What has changed in this forest recently?

Where is the soil disturbed but not destroyed?

Those questions often lead me to morels when others come back empty-handed.

Prime Forest Types Where Morels Thrive

They don’t simply grow in any woods. They favor environments that balance moisture, canopy cover, and soil fertility. Understanding these forest types gives you a sharper eye when you step into the field.

Deciduous Forests:

These broadleaf woodlands, rich with seasonal leaf litter, create ideal conditions for morels. The yearly cycle of leaf fall adds organic matter, building the loamy soils they prefer. The partial canopy in early spring also allows enough sunlight to warm the forest floor, triggering fruiting.

Mixed Hardwoods:

Forests where multiple tree species grow together—oak with poplar, maple with ash—offer diverse ecological niches. The variation in shade, root chemistry, and leaf litter depth creates microhabitats that morels can exploit. I’ve found these mixed stands often yield the most surprises, precisely because of their complexity.

Post-Fire Conifer Forests:

After a wildfire, conifer forests undergo dramatic change. Charred soil, nutrient release, and reduced canopy cover create conditions where black morels often flush in abundance. This isn’t just chance—it’s ecological succession at work. Morels are among the first fungal colonizers to reclaim burned ground.

Riparian Forests (Floodplain Zones):

Forests that edge rivers or streams hold steady moisture and nutrient-rich soils deposited by seasonal floods. This balance of fertility and dampness, combined with periodic disturbance, provides reliable fruiting environments for morels.

What ties all these different forests together is that they are always changing and renewing themselves. Whether the changes are caused by:

- Leaves falling in the autumn

- Different types of plants and animals

- Forest fires

- Rivers changing their course

Essentially, morels are opportunists. They show up where the forest is in a state of renewal. This unique ability to take advantage of change is why they are so hard to predict, and why finding them feels so rewarding.

Tree Associations: The Forager’s Compass

If there’s one shortcut to finding morels, it’s this: follow the trees. Morels often grow in close connection with certain tree species, either living near their roots or feeding on their decaying wood. When you know what trees to look for, the search becomes less random and more intentional.

- Elm Trees: When elms are sick or dying, morels often fruit in large numbers around their bases. It’s almost as if the mushroom is recycling the tree back into the soil.

- Apple Trees: Old apple orchards, even long-abandoned ones, can be hotspots. The soil around them tends to be rich with organic matter, which favors morel growth.

- Ash and Oak Trees: Both can support morels, though the relationship is less predictable. Still, areas with ash or oak are always worth a closer look.

- Poplars and Cottonwoods: These moisture-loving trees, especially along forest edges or near water, can also create the right conditions.

Scientists explain these links through two main strategies:

- They act as decomposers: Morels help break down dead plants and other organic material, recycling nutrients back into the soil.

- They help trees: Morels can also form a partnership with trees, sharing nutrients in a mutually beneficial relationship.

A common saying is that “morels fruit when lilacs bloom” or when oak leaves are “the size of a mouse’s ear.” That may sound folksy, but it’s actually a reliable way to track how trees and fungi respond to the same spring cues.

Looking up into the canopy is just as important as scanning the forest floor. The trees often tell you when you’re in the right place before the mushrooms ever appear.

Soil, Slope, and Microhabitats

If trees are your compass, then soil and terrain are your map. Morels favor loamy soils—rich, crumbly earth that holds moisture but doesn’t drown in it. Heavy clay rarely works, and sandy soil tends to dry too fast. The sweet spot is a fertile mix with plenty of decaying organic matter, often found in leaf-littered bottoms or floodplains.

Slope orientation matters, too. Early in the season, south-facing slopes warm faster, pushing morels to fruit sooner. As spring progresses, the flush shifts to north-facing slopes, where cooler, damper conditions extend the season. I’ve walked entire ridges where one side was picked clean, yet the opposite slope held baskets’ worth because foragers didn’t bother to check both.

Microhabitats are the overlooked key. Look near:

- Piles of fallen leaves that trap warmth and dampness.

- Rotting logs and stumps, where fungi thrive on decay.

- Old floodplain soils that stay fertile and moist after spring rains.

Ecological studies on disturbance and soil quality highlight how fungi often respond to localized conditions rather than broad landscapes. That explains why two people can walk the same woods and only one comes back with a haul—the successful forager noticed the subtle micro-scale indicators others ignored.

Disturbance and Regeneration Sites

If you want to stack the odds in your favor, learn to read signs of disturbance. Morels thrive in forests that are changing, not in static, undisturbed stands.

Burn sites are the most famous example. After wildfires, black morels often flush in staggering numbers. This isn’t a coincidence—it’s ecological succession at work. According to the U.S. Forest Service research, fire releases nutrients, clears competing vegetation, and alters soil chemistry in ways that favor morel fruiting. Foragers call them “fire morels,” and they can carpet an area for a year or two after a burn before disappearing as the ecosystem stabilizes.

Logging zones tell a similar story. When canopy gaps open, more sunlight warms the soil, creating just the right conditions for morels. Even road construction or soil disruption along trails can trigger smaller flushes. I’ve found morels on the edges of logging debris piles, where decaying wood and bare soil come together.

But disturbance comes with responsibility. Overharvesting in these fragile sites can damage regeneration cycles.

These places—burn scars, logged clearings, riverbanks shifting after floods—are where you can feel the forest’s resilience. Morels are the visible sign of the ecosystem healing and resetting itself.

Regional Hotspots in North America

While the general rules of tree association and soil conditions hold true everywhere, the best places to find morels are deeply regional. Climate, forest composition, and disturbance history all play a part.

- Midwest and Great Lakes: Known as the heartland of morel hunting. Deciduous floodplains and river bottoms rich in cottonwood, sycamore, and elm are especially productive. Old apple orchards—though declining—are still legendary hotspots.

- Appalachians: Tulip poplar and oak forests often deliver strong flushes on these slopes. The varied terrain also provides a staggered fruiting season; morels at low elevations appear weeks before those higher up.

- Rockies: Here, it’s less about elm and ash and more about fire. Burn morels in lodgepole pine and Douglas fir forests after wildfires can yield extraordinary harvests. These events create temporary hotspots that can last one or two seasons.

- Pacific Northwest: Post-fire habitats in conifer-rich landscapes (larch, fir, pine) are the gold standard. Damp river valleys and mixed forests also provide steady foraging opportunities.

Regional timing matters. Soil warms later in northern latitudes and higher elevations, so fruiting windows shift accordingly. In practice, this means the morel season moves north and uphill as spring progresses. From a planning perspective, seasoned foragers often follow this seasonal wave, starting early in southern states and finishing weeks later in the northern woods.

My bias leans toward burn sites in the West. There’s nothing like walking a charred slope where blackened trunks are dotted with honeycombed morels. It feels like witnessing renewal firsthand.

Foraging Ethics and Legal Considerations

The U.S. Forest Service makes it clear that many national forests require permits for morel collection, especially in post-fire areas where high demand draws commercial harvesters. Even in places without explicit permits, local rules may limit the volume collected. Checking regulations before heading out isn’t just smart—it’s part of responsible stewardship.

Sustainability also comes down to method:

- Cut vs. Pull: While some argue pulling doesn’t harm future fruiting, cutting at the base with a knife minimizes soil disturbance.

- Carrying method: Mesh bags are recommended because they allow spores to disperse as you walk, potentially spreading future growth.

- Leave No Trace: Avoid raking the forest floor or overturning soil in search of hidden mushrooms. These actions can destroy fragile mycelial networks.

Foragers must recognize that morels aren’t just personal treasures; they’re integral to forest recycling and regeneration. The rule is simple: never take more than you can use or store. Always leave a patch looking as undisturbed as you found it.

Tips for Successful Morel Hunting in Forests

Even with knowledge of ecology, trees, and habitats, there’s an art to spotting morels. These mushrooms are masters of camouflage, blending into leaf litter so well that I’ve stepped past dozens before finally noticing one. Over the years, I’ve learned some practical tips that consistently make a difference:

- Watch the Weather: Warm rains followed by sunny days often spark flushes. If you see a stretch of damp, mild weather in spring, the odds go up dramatically.

- Check Soil Temperature: A cheap soil thermometer can be a game-changer. When readings hit 50–60°F, it’s time to start walking the woods.

- Train Your Eyes: Morels look like pinecones, leaves, or bark fragments at first glance. I tell beginners: once you find one, stop. Scan slowly. Morels rarely appear alone. If one is there, others are nearby.

- Use Natural Landmarks: Pay attention to slopes, tree bases, and floodplain edges. Over time, your brain learns to spot “the pattern.”

- Safety First: Be absolutely sure of identification. False morels can be toxic. They have irregular, brain-like caps compared to the uniform honeycomb of true morels.

The thrill of foraging lies in this blend of science and intuition. Fungi follow ecological rules, but in the field, it often comes down to observation and patience.

I’ve spent hours scanning an empty hillside only to stumble on a cluster that seemed to appear out of nowhere. The truth? They were there all along—I just hadn’t learned to see them yet.

Closing Thoughts

These mushrooms appear where the ground is shifting, where trees are aging, or where fire and water have reshaped the land. Once you understand that, the hunt becomes less of a gamble and more of a dialogue with the woods.

Morels are the proof that forests renew themselves, and by foraging thoughtfully, we get to be part of that cycle without disrupting it.

If there’s one truth I’ve learned, it’s this: the secret to finding morels is patience—not just with the hunt, but with the forest itself.